“After Captivity” is a long-form visual and journalistic project that bears witness to the lives of Ukrainian prisoners of war after their release from Russian captivity. With over 9,000 people still held and exchanges happening sporadically, these stories urgently demand to be documented and told — especially as the treatment of prisoners of war and civilian hostages has grown increasingly brutal since the full-scale invasion. Through portraits, interviews, and observational photography, the project captures the visible and invisible scars, exploring themes of trauma, survival, reintegration, and the search for justice. “After Captivity” seeks to confront the brutality inflicted in captivity, amplify survivor voices, and push for accountability and systemic change through public and media attention. It reveals the human cost of war beyond the battlefield, offering an intimate portrait of resilience, silence, and loss — and of enduring hope for recovery, justice, and healing.

The scars “Glory to Russia” and “Z” were carved on the body of a Ukrainian prisoner of war by a Russian surgeon during a surgery operation in one of the Donetsk hospitals with a surgical laser next to the postoperative scar, in 2024. Andriy, on whose body these scars are, found out about them after he woke up from anaesthesia.

In this photo taken on Wednesday, October 9, 2019, Bogdan Sergiets, former resident of Donetsk, shows a swastika scar on his back in a photographer’s studio in Kyiv, Ukraine. Sergiets was captured by Russia-backed militia in his workplace in Donetsk in May 2014, he spent 10 hours in captivity, tortured and beaten, and his captors engraved the swastika on his back. They also removed his two fingernails, which later naturally restored. Bogdan recalls his tormentors discussing that he should not be released alive after this, in order not to let their actions be given to a public eye. According to former captives, most of the people who had their bodies damaged either way usually weren’t let survive the captivity.

Dmytro Kluger poses for a portrait in his Kyiv home on August 5, 2019. Dmytro was a former resident of Donetsk. He was a civilian when he was captured in May 2014. While in captivity, he attempted suicide to avoid giving up Ukrainian volunteers under repeated torture. Later, Dmytro joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine and defended Kyiv, Severodonetsk, and Bakhmut. He went missing in November 2023. Thousands of Ukrainians are missing as a result of the war, and some are occasionally found in captivity.

Dmytro Kluger poses for a portrait in his Kyiv home on August 5, 2019. Dmytro was a former resident of Donetsk. He was a civilian when he was captured in May 2014. While in captivity, he attempted suicide to avoid giving up Ukrainian volunteers under repeated torture. Later, Dmytro joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine and defended Kyiv, Severodonetsk, and Bakhmut. He went missing in November 2023. Thousands of Ukrainians are missing as a result of the war, and some are occasionally found in captivity.

Olga poses for a picture for the “After Captivity” project in a park in Kyiv, Ukraine, on October 26, 2019. She was captured not far from her home in Alchevsk, Lugansk region, in August 2014. Olga prefers not to remember the dates and duration of her captivity, but she says that despite her “relatively mild” captivity of 10 days, during which she endured three mock executions with a machine gun and once had a grenade thrown into her t-shirt in the Lugansk region in 2015, she developed depression. Initially, she did not realize what it was and thought she was physically ill for two years until she met a psychologist who explained her condition.

Maria Varfolomeieva was a journalist in her native, occupied Lugansk when she was captured in 2015 for taking pictures. She spent 419 days in captivity—over a year and a half. After her release as part of a swap, she went to university and earned a degree in psychology. She was living in Kyiv when the large-scale invasion began and left to avoid the danger of reliving the horrors she had experienced earlier.

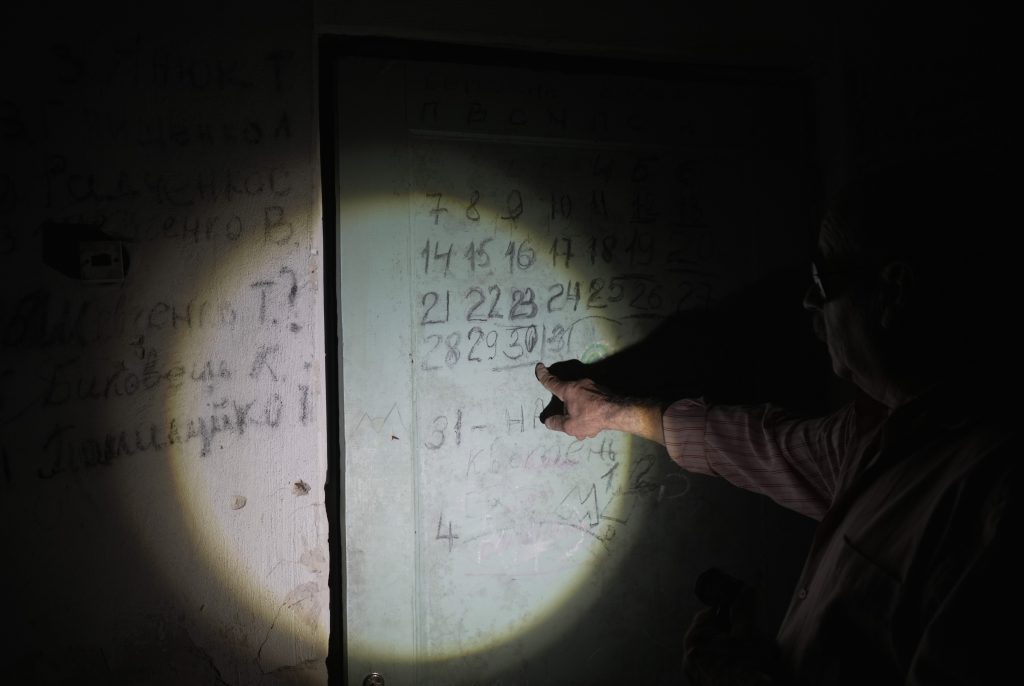

A former inmate of the basement of the school in Yahidne, north Ukraine shows graffiti on the door marking March 30, 2022, the day before the Russian troops withdrew and the captives were released. In this basement soldiers of the 228th Motorized Rifle Regiment, military unit No. 55115, held more than 300 villagers captive for almost a month. People were aged from 1.5 months old to 93 years old. During the month in captivity 11 people died in the basement.

Orest, a Ukrainian soldier, says he was regularly beaten for his Ukrainian name and was often called “khokhol” (a derogatory term used by Russians for Ukrainians) and “Greek.” As a former psychologist, he tried to support his fellow inmates by attempting to create an illusion of normality through retelling movies, sharing gossip, and trying to make jokes. He even tried to teach irregular English verbs to his inmates to distract them from the horrors of prison. Orest was in captivity from August 2022 until April 2023.

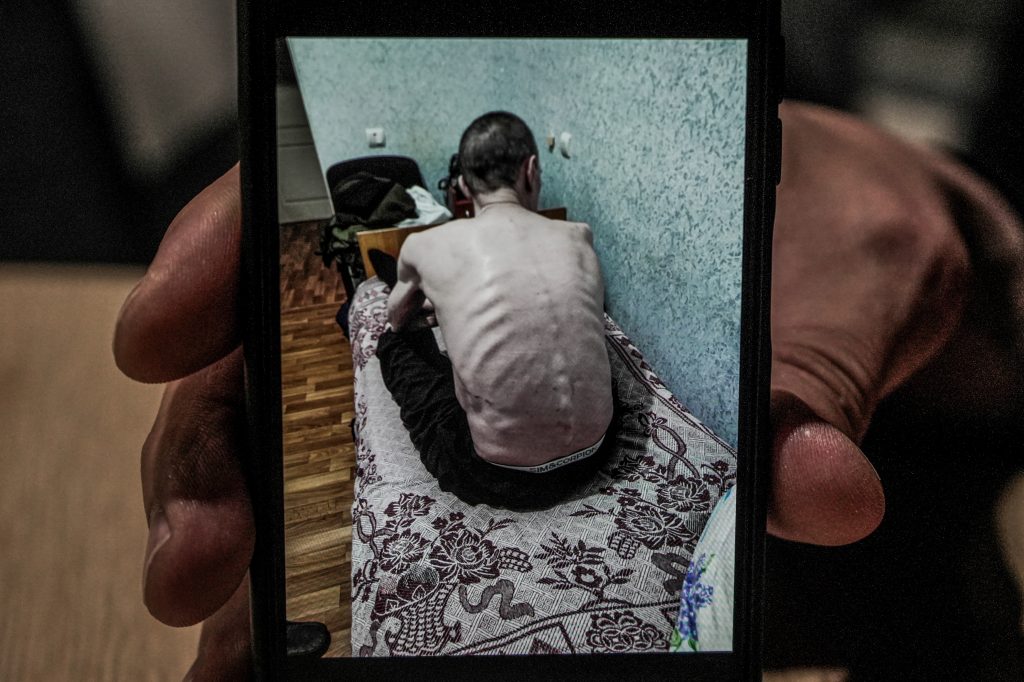

In this photo taken on Sunday, September 1, 2019, Vitaly Paraskun demonstrates a photo of himself just after his release from captivity, in a church in Kyiv where he serves, Ukraine. Paraskun was captured in October 2014 in the occupied part of the Luhansk region while conducting missionary work as an Evangelical priest. He spent 199 days in an unheated basement, enduring regular torture. Paraskun recalls moments when he faced potential execution without fear, but was deeply affected when threatened with harm to his knee. After his release he moved to live in Dymer near Kyiv, which was occupied in 2022, and Vitaliy experienced powerful flashbacks until he escaped the occupation.

Ukrainian serviceman, who asked to stay anonymous for the safety of his family, shows picture of himself at once after his release in 2024 after almost two years in the Russian captivity.

Yulia embraces her husband, Olexander Korinkov, a Ukrainian soldier and prisoner of war, who was released after a prisoner exchange, upon his arrival at Boryspil airport, outside Kyiv, Ukraine, on Sunday, Dec. 29, 2019. Olexander was taken captive one month after their wedding. For five years, Yulia fought for his release. Pictured are the first moments of their reunion after five years apart. Thousands of families are still waiting for their loved ones.

Tetiana kisses the urn containing the ashes of her husband, Olexander Aisin, on 24 August 2019. Aisin died from a heart condition caused by the harsh conditions he endured in captivity, a year after his release. It is tragically common for former captives to die soon after the release, as the extreme suffering they endured leaves lasting damage to their health.